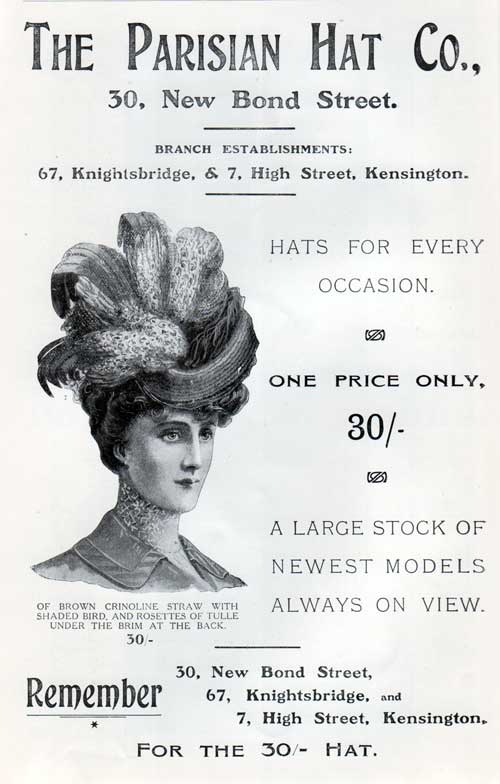

An add for bird hats from the Pariasian Hat Co. From: http://www.gjenvick.com/images/Fashions/1907/CunardDailyBulletin/Adv-TheParisianHatCo-500.jpg.

An add for bird hats from the Pariasian Hat Co. From: http://www.gjenvick.com/images/Fashions/1907/CunardDailyBulletin/Adv-TheParisianHatCo-500.jpg. A hat adorned with what appear to be egret feathers. From: http://www.villagehatshop.com/artman2/uploads/1/the-paris-hat.jpg

A hat adorned with what appear to be egret feathers. From: http://www.villagehatshop.com/artman2/uploads/1/the-paris-hat.jpg

This is the first of two posts that will be on the large number of birds killed for either “science” or for fashion. This one will focus on birds killed for the “sake” of “fashion.”

According to Jennifer Price, writer for Audubon magazine, “[i]n 1886 Frank Chapman hiked from his uptown Manhattan office to the heart of the women's fashion district on 14th Street, to tally the stuffed birds on the hats of passing women. Chapman, who would later found the first version of this magazine, was a talented birder. He identified the wings, heads, tails, or entire bodies of 3 bluebirds, 2 red-headed woodpeckers, 9 Baltimore orioles, 5 blue jays, 21 common terns, a saw-whet owl, and a prairie hen. In two afternoon trips he counted 174 birds and 40 species in all” (Price 2004). At this point in time hats were even adorned with small mammals and reptiles, proving just how bizarre women and “fashion” can become!

Hats were a popular accessory well before bird parts adorned them. Once “bird hats” became popular, milliners would set up “plumassiers,” where feathers were dyed and arranged before being placed on the hat (Thomas 2008). By the late 1890s hats were adorned with entire terns and pheasants, up from the entire songbirds worn in previous years. This inspired one Chicago reporter to state “[i]t will be no surprise to me to see life-sized turkeys, or even . . . farmyard hens on fashionable bonnets before I die” (Price 1999). In an effort to appease women’s “feather lust” men nearly decimated populations of snowy and great white egrets, terns, reddish egrets and roseated spoonbills. An 1875 edition of Harper’s Bazaar contained an ad discussing a new fad. "The entire bird is used, and is mounted on wires and springs that permit the head and wings to be moved about in the most natural manner." An 1892 order of feather by a London dealer (either a plumassier or a milliner) included 6,000 bird of paradise, 40,000 hummingbird and 360,000 various East Indian bird feathers (McDowell 1992, quoted in “Hats off to birds”). In 1902 an auction in London sold 1,608 30 ounce packages of heron plumes. Each ounce of plume required the use of four herons, therefore each package used the plumes of 120 herons, for a grand total of 192, 960 herons killed (Haug 2006).

This came on the heels of the first wave of bird hat boycotts. These boycotts were lead by Harriet Hemenway, a prominent Boston society woman, and her cousin Minna Hall. An 1896 description of the bloody mess hunters made of egret rookeries (nesting colonies) spurred her disgust. At a series of afternoon teas Hemenway convinced other society women to boycott the atrocious hats. Hemenway and Hall also convened a group of prominent men and women to create the Massachusetts Audubon Society. According to Price “On average, women accounted for about 80 percent of the membership and half the leadership, and almost all the "local secretaries," who organized members in each town” (Price 2004). Thus women became conservation activists, often alongside the men in the groups. Women hit the pavement, garnered support and members, organized fundraisers, etc while their male counterparts toured and gave lectures on the importance of conservation. Wearing hats with dead bird parts became morally wrong, at least in the upper class. Lower and middle class women, delighted at the new found affordability of these icons of fashion, were quickly and harshly chastised for wearing the hats. They often couldn’t afford memberships to the upper class societies, and needed to work to feed their families anyway. Still . . . this seems to have been the beginning of a good thing, twisted as it may be.

This reminds me of Hazel Wolf. Wolf was not a society woman, in fact she came from a very poor family. Born in the late 1890s she was an activist for all manner of humanitarian efforts, until she had “run out” of things to do there and moved on to environmental efforts. I love being a woman, particularly when I read about the amazing things we’ve done. I also dislike being a woman, particularly where materialism (which I know is created and encouraged by men) and “fashion” are concerned. Tune in next week for the scientific end of this deadly time for birds.

Thomas,P. 2008. Available at: http://www.fashion-era.com/hats-hair/hats_hair_1_wearing_hats_fashion_history.htm#Plumassiers.> Accessed September 29, 2008.

Haug, J. 2006. “Wings, Breasts and Birds.” Available at: http://www.victoriana.com/Victorian-Hats/birdhats.htm.> Accessed September 29, 2008.

Novia Scotia Museum of Natural History. 1998. Available at: http://museum.gov.ns.ca/mnh/nature/nsbirds/feat05.htm.> Accessed September 29, 2008.

Price, J. 2004. “Heritage.” Available at: http://audubonmagazine.org/features0412/hats.html.> Accessed September 29, 2008.

Homemade Greek Yogurt

9 hours ago

2 comments:

that was up there with those lovely croc and gator pocketbooks.sick.

I think it's really sad when people kill animals purely for fashion. I understand that sometimes animals are killed to be used for good reason, but I don't think that it should be to decorate a hat. So sad...

Post a Comment